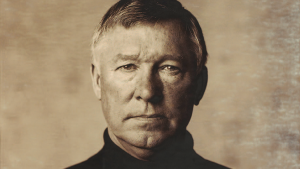

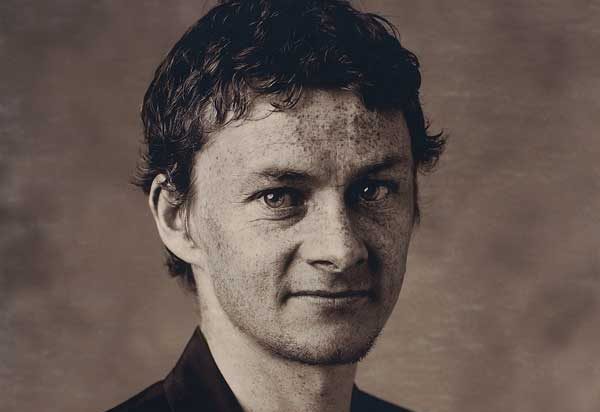

The Baby-Faced Assassin

Ole Gunnar Solskjaer has popped up in some unexpected places in his time at United, where the ability to score match-winning goals and his level-headed manner have made him a huge favourite with the fans

How may a life transform in the time it can take traffic lights to change? How can history turn, legends be writ in 131 small seconds? Match pace. The president of UEFA is on his way to present the European Cup. When he gets in the lift to go from the VIP enclosure at the Nou Camp to pitch level, Bayern Munich are winners. When the doors open at the bottom, he can’t understand why United are cavorting and the German team is in tears. What makes this possible? Match pace.

Ole Gunnar Solskjaer and Samuel Kuffour wait for a corner. Kuffour is holding Solskjaer’s shirt and there’s no way he’s letting go. An instant later, Solskjaer is yards away, touching the ball into the net. For 92 minutes, Kuffour has been perhaps the best player on the field: what was he thinking? How did Solskjaer escape? Why is Kuffour crying, beating his fist upon the grass so violently that he sprains his wrist? There is ordinary time, and then there is match pace.

Here’s a secret. Barcelona was not the first time Ole Gunnar Solskjaer scored the winner in a European Cup final. Or even the hundredth time. “I’m quiet, but I’ve always had loads of belief in myself. If the chance is there, I can finish it,” Solskjaer says. “It doesn’t matter the situation, I’ve been training myself since I was young.

“If you hit the bottom corner, it doesn’t matter if there’s a 14-year-old keeper or a 30-year-old – he won’t save it. So in training, even though it looks stupid sometimes, I always do things at match pace. You’re on your own, you take one, two, three, four, five touches, fanny about and score a goal… there’s no point. Do it as if it’s a game. Do things at match pace. “I’ve done it since I was a boy. I’ve played many European Cup finals on my little pitch, said to myself thousands of times: ‘There’s one minute left, touch, score…”

Kristiansund is a lovely but tiny town, spread across three small islands in a fjord far up Norway’s west coast, more or less on a latitude with Iceland. Its people are understated and wry. Drily, they call the biggest – or rather, the least little – of their islands ‘Morocco’ and the smallest ‘Tahiti’. Here, Solskjaer was raised. Near his house was a patch of ground, gravel and sand. Not much, but it had two posts and a net: his “little pitch”.

Later he played at the modest town stadium for Kristiansund’s little team. There was no headlong, headline-making rush for the big time. Instead, Solskjaer proceeded slowly and quietly, not leaving for the ‘bright lights’ of Molde (population 24,000) until he was 21, not even reaching the Norwegian First Division until he was 22.

Solskjaer owes his values to Kristiansund. In football he takes his philosophy from Ole Olsen, his first coach. Every time Solskjaer plays for Manchester United, back in Kristiansund Olsen will study the video and email a critique to his protégé. “You have to improve little by little by little, all the time: that’s Olsen’s way of thinking. He gives me the plus points, and the negatives too. It’s important, because the worst thing is to have ‘mates’ who say: ‘You were great,’ even though you know you were shit.”

Solskjaer’s personality – sensible, low-key, but humorous once you know him – is surely another product of Kristiansund. His parents didn’t travel to the 1999 European Cup final. “They had work the next morning. They’re very down to earth,” he smiles. “My dad’s a payroll accountant for the council and he’d already been to the FA Cup final the week before. But that was a weekend – you don’t take a day off just for a match! In Barcelona it looked like I might not play anyway. I’d only be on the bench…”

This don’t-fuss mentality is perhaps the reason it took Solskjaer until late 2005 before he felt able to embrace the legend he created on May 26, 1999. Being ‘the man who won the European Cup’ used to offend his sense of perspective (“I was only on the pitch for 13 minutes…” he groaned during a previous interview). The ‘supersub’ tag affronted his distaste for hype. Not unreasonably, it annoyed a footballer who would still have had a heroic career even if he’d never scored a single goal after coming off the bench. Who wants to be seen as just a substitute when, without taking penalties, and having operated latterly in midfield, your scoring record as a starting player (once better than Thierry Henry’s) remains better than Dennis Bergkamp’s?

But Solskjaer has made peace with the idea now. “If that’s how I’m going to be remembered, as a ‘supersub’, I’ll be happy,” he says. “I’ve changed. When you’re young you feel different. Of course I’ll continue to think, like I always have, that I do a good job playing from the start, but I don’t mind being called ‘supersub’ any more.

“And it’s strange to think that I’ll be an old man, and I’ll be meeting United fans, and they’ll still want to talk to me about that goal, but I’ve got used to it. I always get asked questions like: ‘How did it feel? You were the one who won it…’ It wasn’t me who won it, it wasn’t my touch, it’s what the team did over the season… but never mind.”

What’s altered? You regard life differently when you have a brush with sporting mortality. The terrible knee injury which halted Solskjaer in 2003, and saw him still straining to recover full fitness in 2006, was a reminder that playing careers are finite and brief. “Once you’re out for a long time and face up to the fact that you may never be a regular starter again, you realise that being a regular substitute is a lot better than nothing. When you’re injured you see things differently and you mature. You realise that every minute you get on that pitch is precious.”

how precious he has been. When Solskjaer arrived at United, aged 23 and still slightly obscure even in Norway, there were giggles at The Cliff. “There were comments. I didn’t hear them at the time, but afterwards I was told some of the players were saying: ‘Here’s a 12-year-old boy and he’s won a prize – a day’s training at Manchester United,’” he grins. He never did look old enough to be deadly, but as soon as shooting practice began, the opinions of his new colleagues changed. On his debut against Blackburn he announced himself to a wider audience by scoring. He’d come on as a substitute and it was a game-changing late goal… It’s one thing recognising an omen, another to act upon it. Over the next six years Solskjaer was to breach opponents’ defences a further 21 times, often to decide the match, after coming off the bench.

He wouldn’t want you to forget that he has scored close to a century of goals as a starting player, but may nowadays permit the observation that 24 strikes as a substitute for United from 1996-2003 is remarkable. And there was something special about 1998/99. His tally was eight goals as a sub, six of which were scored from the 80th minute onwards in games. Four of these came in an 8-1 win against Nottingham Forest on 6 February. (“They were 4-1 down, all over the place, not a normal match situation… when it’s like that it doesn’t matter if you come on and score four or none at all,” he says with typical diffidence.)

A fortnight earlier, in the fourth round of the FA Cup against Liverpool, a sobriquet had been born. With two minutes left of the tie, United were behind but won 2-1, Solskjaer scoring in injury time. Sound familiar? “My only touches were one to collect the ball from Scholesy and one to put it in the net,” he says. The next day’s newspapers, for the first time, prefixed his name with ‘supersub’.

Ninety-nine per cent of being an assassin is the waiting, only one per cent the actual kill. Ferguson has never seen a player better at sizing up a game from the sidelines. Watching is an art and a state of mind. “My mates have always told me I’m too sensible. Of course I’d rather start games, but whenever I’ve been sub I’ve said: ‘Okay, you wanted to start, but move on – and do your best when you get on the field.’ If I come on later in a game, I’ll be fresh and the other players will be tired. I’ve always tried to see the positive side.

“First and foremost I enjoy watching football. As a striker, you know there’s a big chance you’ll come on during a game – it’s not like being a keeper or defender on the bench – and I sit there and try to analyse teams. I say to myself: ‘If I get on, who are the weak and strong players?’ I remember coming on and scoring against Leeds United once. I’d seen Rio Ferdinand [who was playing for Leeds] win nearly everything in the air, so when there was a cross I spun off so I could jump against Ian Harte instead. There’s nothing dramatic about what I do, it’s just noticing sensible things like that.” During Solskjaer’s long rehabilitation from his knee injury, Ferguson made use of his analytical gifts by asking him to train United’s youth players. “I want to be a coach,” says Solskjaer, “and I’ve kept a written record of almost every training session I’ve done in my career so I can use the routines in the future.”

His best substitute appearances? “Forest was just a training session, I don’t count that. I did all right against Tottenham at White Hart Lane [in 2001]. We were 2-0 behind when, five minutes before half-time, the gaffer put me on down the left. I stayed a bit too high up the pitch and they scored another one. At half-time he mentioned a few things to me and in the second half I positioned myself better. I did really well with my movement and we won 5-3. But the most important one has to be against Bayern.”

In Barcelona, Solksjaer had a premonition. “I was rooming with Jaap Stam, as usual, and he was taking an afternoon nap. I couldn’t sleep so I watched a bit of a DVD and then called one of my closest friends back in Norway. He couldn’t make it to Spain, so I wanted to check if he was going to watch the game. He said: ‘Yeah, but I’m going to have to leave 15 minutes from time.’ He’s a nurse and he had the night shift.

“I told him he had to watch the whole game: ‘Get someone to step in for you for an hour.’ Because I had this feeling something big was going to happen to me. It’s hard to explain, it was just a feeling. It’s about positive thinking, maybe; you always visualise yourself scoring, so perhaps that’s all it was. But it was a little bit of a stronger feeling this time. I don’t know why.”

Solskjaer mentioned his feeling to Jim Ryan, United’s coach, but Ferguson had his own thoughts about which players might have a special day and started with Andy Cole and Dwight Yorke. This was no surprise, for in tandem they had terrorised Europe all season. But Bayern, having scored early, retreated, banking their midfield in front of their defence. Yorke was denied the space in front of the centre-backs that he liked and Cole the room in behind. After 67 minutes Ferguson made a change: Jesper Blomqvist off, Sheringham on. “I remember [Ferguson] saying to Teddy at half-time to get ready and thinking: ‘Why’s he not putting me on?!’ and as the game continued the thought was running through my head: ‘Put me on!’ I was just waiting and waiting for the gaffer.”

It was then that Solskjaer pulled another important substitute’s trick. Poor old Phil Neville, he never learnt the knack. There were fewer sub appearances in Das Boot than in Neville’s United career, but many times Neville worked up and down the Old Trafford touchline with exemplary commitment without getting on. “There’s a technique to it!” Solskjaer laughs. “In the first half you just warm up. In the second it’s different.

“You can always tell how I’ll play by the way I run on. When I’m heavy-legged I can tell I’m not on song, and my friends can spot it too. But entering the field that night I was springy, I was bounding on…everything felt good”

When you sense the gaffer’s going to do something, you make sure there’s a spring in your step, that you’re putting in a good stride when you’re running up and down the side of the pitch, so that when [Ferguson] glances to the subs you catch his eye.” Solskjaer went through this routine at the Nou Camp. Finally Ferguson gave him the nod. With the clock showing 80 minutes, Solskjaer entered the European Cup final.

Only once has he watched, in its entirety, footage of his 13 immortal minutes. He does not own a commemorative video of the final, but at home his dad keeps an old, worn VHS cassette, labelled in ballpoint pen, on which he taped the game. Solskjaer has a tip for anyone watching film of the game. “When I come on you can see there’s a step, a rhythm in my running. You can always tell how I’ll play by the way I run on. When I’m heavy-legged I can tell I’m not on song, and my friends can spot it too. But entering the field that night I was springy, I was bounding on… everything felt good. My only thought was positive: ‘Come on, get a goal.’”

Before Solskjaer appeared, United hadn’t had a single attempt on target. Within seconds he changed that, bringing a good save from Oliver Kahn with a near-post header. Soon he sent Sheringham through, but his partner shot weakly at the goalkeeper. Then Sheringham equalised. “It’s two miskicks: Giggsy miskicks and Teddy finishes with a miskick… I think, although he might not admit it! Everyone went mad. Everyone crowded round Teddy, even Peter Schmeichel, who was up for the corner – except me. I headed back to the halfway line, concentrating. I was focused. I thought: ‘Now you’re going to play another half an hour [of extra time], don’t waste your energy chasing Teddy.’”

Match pace. “There’s a long diagonal pass to the left wing. I run over from the right wing to reach it, Kuffour comes with me, I try to get past him with a stepover but he gets a foot in. It’s a corner. We run into the box. He’s got a hold of me. He’s grabbing me all the time. The cross comes and it’s nowhere near us – it goes to the near post – so he lets go of me and looks at Teddy, and that just gives me the half-yard I need to move away from him.

“The goal? It’s one of those that you score one time out of five if you’re lucky, because you haven’t practised that finish. You just do it. You just guide the ball on. More often than not it goes over the bar… and there’s a man on the far post so, other times, you won’t guide it above him. There were so many things that could have gone wrong with that finish… it was just instinct. Perhaps I’d done that finish once when I was younger. Perhaps there was some muscle memory there.” Perhaps it was just the power of premonition, uncoiling at match pace.

Season 1998/99 was an odd one for Solskjaer. After his extraordinary debut campaign of 1996/97, when the 12-year-old boy who won a prize ended up scoring 19 times, he lost his way in 1997/98. There were injuries and, possessing a surfeit of enthusiasm and a deficit of experience, he kept coming back too quickly and never felt right. Early in the Treble season he played one of his few games in tandem with Dwight Yorke against Charlton; they both scored twice, but the potential of the partnership was never explored. Once Cole and Yorke got together, Solskjaer and Sheringham could appreciate the obvious. “Dwight and Andy clicked, they were a combination. Me and Teddy talked about the situation. We weren’t unhappy.” Wes Brown, then a teenage rookie, made more European starts in 1998/99 than Solskjaer. “I didn’t play a single minute in either leg of the quarter-final or semi-final and played in just three of the group games. I hardly started a match all season apart from in the FA Cup, and yet I was the one who got to score the winning goal… funny how it works out.

“That’s why, in many ways, 2002/03 was more precious to me. It was the first season I played myself into the position of being a first-team regular and we won the title. That season gives me more pleasure than that one goal in Barcelona… but obviously, in terms of the club’s history Barcelona was more important.

“It’s a corner. Kuffour’s grabbing me all the time. He lets go of me and looks at Teddy, and that gives me the half-yard I need to move away from him. The goal? It’s one of those that you score one time out of five if you’re lucky. It was just instinct”

I used to find it difficult even to talk about 1999. You could ask Lars Ricken how it feels. He wasn’t a regular for Dortmund but scored in the 1997 final, and I bet he’s always asked about that. It’s logical but, for me anyway, you’ve done it, you move on, you play in the next game. Barcelona was much greater for my dad, seeing his son score that goal, than it was for me. For me the next game, next training session even, is the most important thing in my career. Dad can live on memories – I can’t.”

At the end of 1997/98 Solskjaer was sent off for a professional foul that prevented a goal against Newcastle and was applauded off the pitch at Old Trafford. That could have been how his United career ended. That summer United accepted a bid from Tottenham for the player. Providentially, he turned Spurs down.

“I’ve still got the fax at home, signed by Martin Edwards and Alan Sugar. They send you a fax to entitle you to negotiate if the two clubs agree a fee. But it didn’t feel right. There was something in my stomach. I didn’t want to leave. My agent did, but I was really stubborn about staying. He’s since admitted I was right… The club agreed to sell me, but what you’ve got to remember is that the club and the manager are two different things. The chairman was happy for me to go, but I went to the gaffer and he said: ‘Stay’, and that’s all I wanted to hear. I could have made some money from leaving, but that wasn’t an issue.”

Solskjaer’s loyalty, his compulsion to stand and fight for the cause, elevated him. During his two years out injured they hung a banner reading ‘20LEgend’ – 20 being his shirt number – from the Stretford End and, at least once every game, fans sang his name. “For me the win in ’68 was bigger. George Best, Bobby Charlton, Kiddo – that’s bigger than our game. But I’m proud to have been part of the making of Manchester United’s history. It’s a fairytale I wouldn’t have believed in when I arrived all those years ago. If you’d told me then what was going to happen to me over the next 10 years I’d have shot you. I’d have said: ‘You’re mad, no way.’

“I came from Kristiansund, playing in front of 50 or 60 people, so I’ve enjoyed every single minute at United – it’s the best place in the world to be. I’ve had friends who’ve left, and everyone has said there’s nowhere quite like here.”

What were Solskjaer’s thoughts as United paraded the European Cup around Manchester after returning from Barcelona? He wished he could stop the bus and go home to Silje, his girlfriend. They’re married now and have two children, Noah and Karna, and his family is the one thing in Solskjaer’s life that’s more important than Manchester United.

“Family. That’s a good word. When you come to Carrington, the first person you meet is Cath on reception, and it’s a smile and a hug. The atmosphere here is not arrogant but inclusive. Somehow United combine being a giant club with having the feel of a small club like Molde. As a new player you immediately feel part of the group, and among the older players there’s a sense that the longer you stay, the more responsible you are for looking after what makes the club special. Players come and go but that spirit lives on.”

Only once did Solskjaer ever complain about being substitute – at the end of 2000/01, when he was named on the bench against Chelsea. “The manager had always said he wanted to see me play a number of matches in a row. I was in the middle of a run, so when he left me out I said: ‘I thought you wanted to see me play more games.’ In the end I played – and scored. That was the only time I’ve gone against him.

“For me, the relationship with the manager is everything. I’ve never ever felt the urge to play for myself. This is the manager’s team; if he picks me, I feel I owe him a good performance. If he doesn’t, fair enough. And if sends me on with 10 minutes left, those 10 minutes are going to be the most important thing for me, not the 80 minutes I don’t play.”

On will come Solskjaer, bounding hopefully and treating every moment of pitch time as precious. And to be performed at match pace.

In the same month that their manager was knighted by the Queen for furthering British achievement abroad, United were branded traitors to their country. Such is the black-and-white existence of football’s biggest club. United’s ‘crime’ was to pull out of the FA Cup to travel to Brazil to play in the inaugural FIFA Club World Championship in January. England hoped to host the 2006 World Cup and the FA (keen to curry favour with FIFA via their top club’s participation in the new tournament) put such pressure on United that there was little alternative. But that didn’t stop righteous indignation from within football and, especially, the media, frothing up and boiling over upon United who, as FA Cup holders who had declined to defend their trophy, were accused of devaluing the game’s oldest knockout competition.

The Daily Mirror even contacted the Vatican for the Pope’s reaction. Beckham said that in the dressing room “we talked about it as much as anyone else,” but also that “sometimes it felt like the whole issue was just being used as an excuse to have a pop at United… I think everybody knew we had to go.” It didn’t help that the new competition was obviously a confection designed to advance FIFA’s agenda. Football already had a perfectly good ‘world championship’ for clubs, with a rich history behind it; the Intercontinental Cup (which later became the Toyota Cup), played for since 1960 between the champions of Europe and South America. Despite nine attempts, no British club had won the trophy; United had failed in 1968, beaten by the brutal Argentinians of Estudiantes.

Ferguson’s team changed all this, travelling to Japan in late November to defeat Palmeiras thanks to a Keane goal and outstanding performances by Mark Bosnich and Giggs. United’s achievement was heightened by the fact that the trip to Tokyo came in the middle of a busy period which also featured big Champions League games against Fiorentina and Valencia, and a Premier League assignment with Everton. Palmeiras, in contrast, had a clear schedule and spent 10 days in Japan prior to the match, acclimatising and preparing.

It’s one thing to defeat Brazilian opposition on neutral soil: beating Brazilians in Brazil must be one of football’s most severe tasks, and it wasn’t something United were equal to in Rio. Despite the grief playing in the Club World Championship had caused them, Ferguson and his players struggled to motivate themselves when, as Keane said, “the exact status of the tournament was vague”. Real Madrid took a similar view and underperformed almost as badly as United, the pre-tournament favourites. The organisation of the event was poor and – with United billeted in a busy tourist hotel on Copacabana Beach – arrangements for the club were unsatisfactory. The vast concrete banks of the Maracana stadium would empty whenever Brazil’s twin representatives, Corinthians and Vasco da Gama, weren’t playing, leaving the other games devoid of atmosphere.

Then there was the heat. They display the temperature on lampposts in Rio, and Giggs recalls the gauges already reading 35°C when United, attempting to avoid the worst of the sun, arrived for training at 8am. It was 40°C and rising by the time they finished, and when United arrived at the Maracana for their first match, against Nexaca of Mexico, players were sweating after walking the few yards from the team coach to the stadium doors. A slow, dull game ended in a 1-1 draw and Giggs felt “knackered” throughout United’s next 90 minutes, in which they were beaten 3-1 by Vasco amid searing temperatures. The side even struggled in a 2-0 win against South Melbourne in their final game and flew home after the group stage. Corinthians beat Vasco in the all-Brazilian final.